Composition over Inheritance: lessons learned

When writing a big piece of software, its architectural design is fundamental, and videogames are no different. Bad design can lead to frustratingly complex and non-modular code, and you might end up rewriting the whole thing from scratch. Since that’s the case of my videogame Lifish, I’m going to share my experience within this topic.

It ultimately boils down to the following advice: when it comes to videogame programming,

This probably sounds familiar to many of you, especially those aware of the ECS paradigm and related stuff, but

it’s a truth worth repeating. For those of you who’re new to this concept (like I was when I started coding videogames),

I’ll try to convince you.

Inheritance is BAD

Inheritance is a core concept in all modern OOP languages; it’s powerful, it enables code reuse, polymorphism, virtual methods and all other kinds of cool features you can think of. That’s certainly true, but it has one problem that really clashes with videogame programming: it’s very. rigid. Let me elaborate on this.

You can think of a project as a collection of class hierarchies. In most OOP programming languages, these hierarchies

are trees, often with a common root which is an Object class or something alike. (That’s not always the case:

in C++, for example, a base class does not exist,

so either you roll your own or you have indeed several unrelated hierarchies, meaning, for example,

you can’t

safely upcast two unrelated classes to a common base. To make things more complicated, in C++ these hierarchies are

not necessarily trees, due to multiple inheritance.)

Given this baseline - which you cannot avoid, at least in an OOP language - creating a new class necessarily means placing it somewhere in some hierarchy. When you’ve done that, your class is frozen in that place, forever. That’s what I mean when I say inheritance is very rigid: you need to make your choice on where to place a class as early as in the process of creating it, and once the choice is made you must either live up with it or rewrite several parts of the project. This option, which is always unpleasant, becomes more and more time-consuming and dangerous as the number of classes in your project grows, until it starts feeling like playing Jenga with code: a wrong move might end up making everything else fall down.

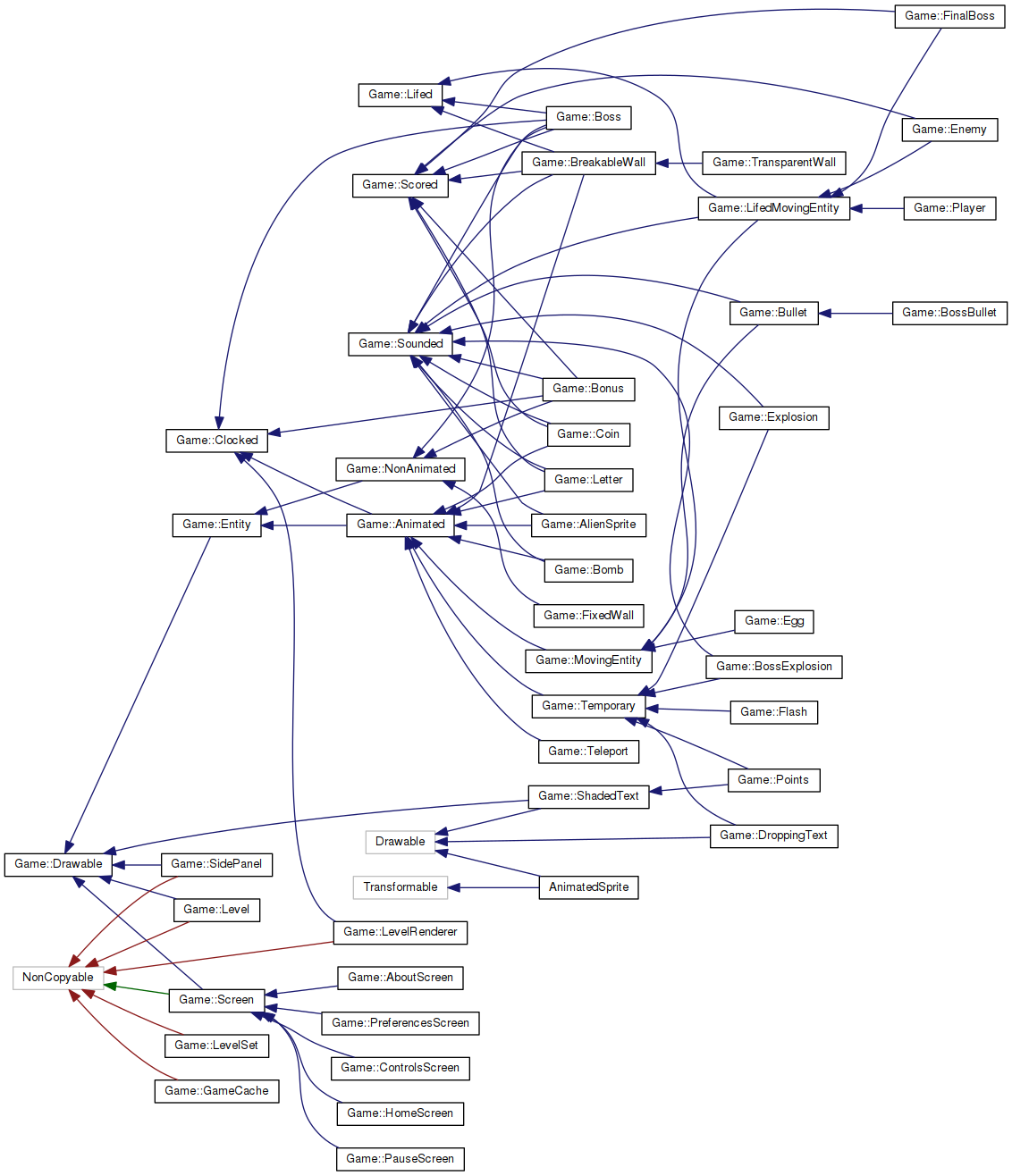

Let me give you a real-life example of this, straight from my first attempt at creating Lifish:

This may not look that bad, but it’s only 45 classes, and it contains utter nonsensical classes as NonAnimated

or LifedMovingEntity (more on that later).

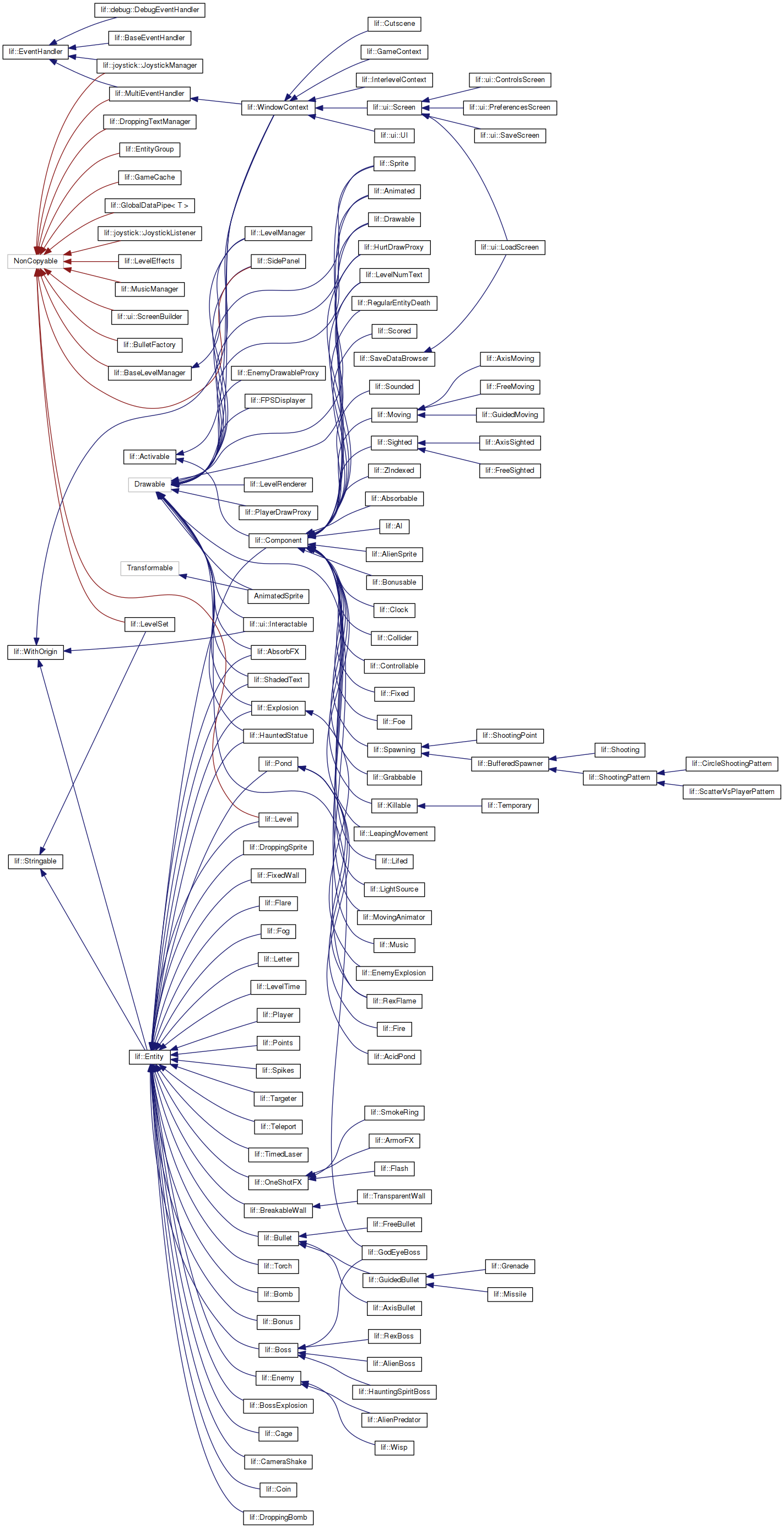

Now compare it to the current Lifish class hierarchy:

Even without knowing the details, you can tell the second picture is much cleaner and more linear, even though it’s well over 3 times as many classes. This can be achieved by adopting the philosophy of Composition Over Inheritance, which I’m going to show you.

Composition is GOOD

Composition is a programming paradigm which aims to augment a class’s behaviour in a pluggable, modular way. Instead of carrying over all the parents’ methods and fields, possibly adding and/or overriding some of them, composition achieves that by adding “delegate classes” to an existing one, each containing one specific behaviour. These delegate classes are usually called “Components”, while the class containing them is often called an “Entity”.

There are several ways to implement this strategy, the most famous being the ECS paradigm, but the one I’m going to illustrate here is the Lifish approach, which is slightly different.

In Lifish, all the gameplay-related classes inherit from Entity. Yes, I know I just said that Inheritance is BAD,

but that was referring to inheritance as a design paradigm, not to all uses of inheritance. If a language

(in this case C++) gives us useful tools, it’d be dumb to refuse them when they come handy. Inheritance is still

very useful in the correct places and amount.

So, what is an Entity?

In the case of Lifish, it’s a class with the following properties:

- it has methods to

addComponents to it; - it has methods to

getComponents (by class) from it; - it can be

updated, typically once per frame; - it can be

initialized if necessary; - it has a

position. This last property is not vital: I could’ve embedded the position as a separate Component, but I decided to put it directly in the base class for convenience.

The interesting design choice in Lifish is to make Component a direct sublass of Entity, so each Component

can contain other Components recursively, allowing great code reuse in a simple way.

Given these base building blocks, any game entity can just be a direct subclass of Entity, differentiating

from the others just by:

- adding different Components to it (typically an Entity will add Components to itself in its constructor), and

- (optionally) overriding

updatein a unique way.

This design principle is so expressive that many game entities don’t actually need to override update at all:

they just add a bunch of Components in their constructor and that’s it!

Composition is a really powerful way to separate behaviour from the single use-cases, really allowing the same code

to be reused over and over. Of course, this is only guaranteed if the programmer is very scupolous not to introduce

dependency between unrelated classes, which is a common temptation when writing gameplay code.

Wrapping it up - for now

I have a lot more things to say on this topic, but I’d rather avoid writing too long of a post, so I’ll just split things across several ones.

The important message I want you to get from this is: when coding a videogame, do yourself a favor and use composition as much as you can. Especially when the final structure of the project is not clear from the beginning (and in my opinion, it never is), pure inheritance-based design is just unfit for the purpose. It can’t keep up the constant changes, improvements and modifications you’ll need to introduce later on, and gives you no real benefit.

When you come up with something like LifedMovingEntity, you know something is going really wrong with your codebase.

If two behaviours which are supposed to be totally unrelated (like “having a sprite to display” and “being able to

shoot”) come up being dependent on each other, your design has some problems. Try to notice these things early and

change them. It’s worth spending some time when the codebase is still small to avoid spending a lot of time

when it’s too late.

Don’t give up on code design. Don’t exceed trading architectural soundness for time. If you take care of your code, your code will take care of you.

As always, thanks for reading. The next post will probably go further into technical aspects of the Lifish core, like how to deal with dynamic type-based querying of Components in C++, so stay tuned if you’re into that stuff :-)